In the Mind’s Eye

At the age of 14, Rene witnessed his mother, being pulled out of the river; her lower body was exposed and her nightdress was over her head concealing her face. Was it her, and if it wasn’t where had she gone, what had happened? But Rene never talked about it; he didn’t trust words. He just expressed it through the medium he had control of; painting. He was an artist philosopher. Perhaps all ‘creative’ artists are. What is art, if not visual metaphor?

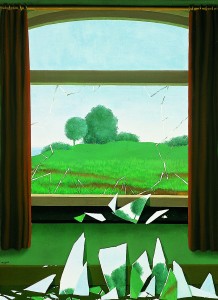

Rene Magritte just took it further. His painterly skill allowed his imagination the freedom to use the image to describe the thought. His images express the way the mind connects ideas. They have a dream like quality because that’s how our mind sees things when we are not fixed by the consciousness of real time and space and the rules of language. So like dreams, his images break the rules, size is relative, shape distorted, there are impossible associations. In The Dominion of Light, he merges light and day, street lights illuminate a street against a bright afternoon sky, a bird flies over a dark sea, its shape filled in by a bright cloudy sky. A crescent moon is placed in painted in front of the dark tree, the artist creates the woman by painting her, the landscape on the canvas becomes the view, the window pane breaks up into pieces of the landscape viewed through it, a couple kiss with cloths over their heads, an act of intimacy between two people who are concealed from each other.

The theme of concealment dominates his work. He creates illusion by representation. Magritte liked a mystery, the anonymous detectives in bowler hats coming to arrest and assailant, the woman’s body on the operating table, the same bowler-hatted figures of differing sizes descending like rain in front of the buildings of his home town.

Magritte wasn’t so much looking for meaning, he was more interested in the process of how we represent ideas; he wanted to express ideas as he perceived them. Our mind, as the extension of the vast neuronal network that is our brain, makes connections between ideas and actions and feelings. Having conceived of a certain way of thinking, we return to it again and again, establishing neural connections like paths through the forest. But our mind’s reality makes connections which are impossible in the real world. Magritte shows us the way our mind thinks about things. So a pipe is not always a pipe but represents something much more potent, a carrot morphs into a bottle, a bird becomes part of the sky, clouds are like object and thoughts.

Magritte recognised how words condition our thought, fixing and channelling the meaning, so he experimented with different words for objects. Words tell us what an object is, but our mind sees other connotations. Poetry plays with this idea. It explores the power of words, but also their limitations. Freud and Jung explored the same territory in their papers on symbolism and dream, but at least Freud had the honesty to admit that ‘sometimes a cigar is just a cigar’.

Magritte, The Pleasure Principle, is currently being exhibited at Tate Liverpool on Albert Dock.