The trainspotter’s guide to survival and forgiveness

What was it about Eric Lomax that enabled him to survive the most extreme imprisonment and torture when so many of his colleagues died? What strength of character allowed him to return to normal job in Edinburgh after such devastating trauma? And how could he actually bring himself to forgive his Japanese interrogator and actually become his friend?

The Railway Man is a remarkable story of courage and forgiveness. John McCarthy, who was himself kept hostage in Lebanon under dreadful conditions, describes it as ‘an extraordinary story of torture and reconciliation. I turned the last page weeping tears of sorrow, pride and gratitude.

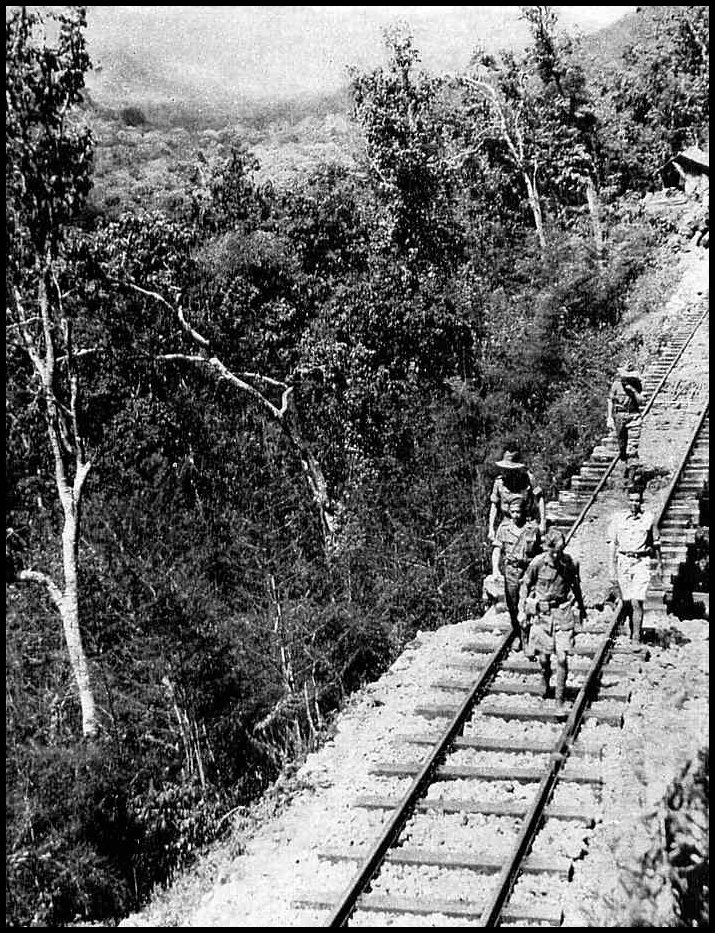

As a boy, Lomax was fascinated by engines. He would travel miles across country just to see one of his beloved machines. Later he espoused religion with the same dedication. He was quiet boy; he got on well enough with other boys, but was never happier than following his obsessions. In 1939, he joined the British Army as a signaller, and was trapped by the Japanese with tens of thousands of other soldiers in Singapore in 1942 and assigned to work on the Burma Siam railway that would carry Japanese territorial ambitions to India. Despite the lack of food, filthy conditions, exhausting physical work in full tropical sun and casual brutality of some guards, the men alleviate their plight by growing or stealing food, dreaming up escape plans and constructing makeshift radios, by which to learn the progress of the war. Lomax continues to derive solace from his contact with the railway and his beloved engines.

But after a tip off, the Japanese discover their radio and the map Lomax has drawn. In the book, he dispassionately describes the beatings with pick-axe handles, during which both arms are broken and his hips and back damaged. He is then handed over to the Kempitai, the Japanese Gestapo, who imprison him in a small ant-infested cage in full sun with only heavily salted rice to eat and subject him to prolonged interrogation interspersed by spells of torture and near drowning by waterboarding. He learns how to raise his pulse to dangerous levels and persuaded his captors to move him to hospital in Changhi where he survives, a living skeleton, until the Japanese surrender.

Lomax was psychologically damaged for years after the war. As his physical condition improved, people ignored the effect of their trauma. In India on his way back, one mem’sahb commented that after a rest, he must be longing to do his bit and get back to active duty. His young wife was more concerned by the privations of rationing than his experience in the far east. Without validation and acknowledgement, it was like it never happened and he withdrew into himself. After another thirty years, the marriage failed.

With the help of Patti, his second wife and Helen Bamber of the Medical Foundation for the Care of Victims of Torture, Eric Lomax finally managed to talk about his experiences. Patti is given a copy of Crosses and Tigers by Nagase Takashi, in which he describes the bravery of a young signals officer he interrogated. It is Lomax. Also traumatised by his experience, Nagase has become a dedicated anti-war campaigner. The two meet. Nagase is overcome with emotion and Lomax finds it in himself to forgive him and even accept him as a close friend.

The Railway Man is indeed a remarkable book. Lomax is remarkable, not for his courage. Courage is inconsequential when the outcome is inevitable. It’s when you choose to do the right thing even though you know you will suffer and even die for it that real courage is needed. No, it’s not courage that Lomax shows but endurance and will to survive. That takes amazing qualities or hope and faith. People have written of how love for their wives or their God maintained their hope. I wonder if Lomax’s obsession with railway engines also provided that focus of imagination that transported him out of the real hopelessness of his circumstances, distracting him and providing the certainty that sustains him through the most dreadful pain and privation. It’s the doubtful, the needy and the insecure that succumb. You can put up with anything as long you have faith in something, because by transference you can then believe in yourself and gain distance from a grievance that allows real forgiveness. To err is human, but to forgive is divine. When people are desperate and fearful of their lives, they are capable of anything. The environment of war breeds inhumanity. Nagase hated what he was doing but was terrified of the reprisals if he refused. Nagase has atoned for his guilt. It was easier for Lomax to forgive him, but few would have done that.

As the Buddhists teach, forgiveness sets you free.