The dread of feeling too much; Edvard Munch and his women

‘I was out walking with two friends. The sun began to set. Suddenly the sky turned blood red. I paused, feeling exhausted, and leaned on the fence. There was blood and tongues of fire above the blue black fjord and the city. My friends walked on and I stood there trembling with anxiety, as I sensed an infinite scream passing through nature.’

The Scream, Edvard Munch’s most dramatic and important work, is a potent symbol of terror, but terror of what; an existential loneliness? – the death of God? – the meaninglessness of materialism? Whatever, Munch projects this unbearable dread and isolation into this painting.

But artists always project their innermost feelings into their work. All creative people do. So why was Munch so anguished? Was it the death of his mother from TB, the combination of love and fear he felt for his father, the death of his older sister from the same dread disease, his own brush with death, or his feelings of guilt and devastation from two failed love affairs? That’s enough trauma for anybody, particularly one as sensitive as Edvard Munch. Love and death dominate his work, but representations of love were never joyous; they were always linked in his art with threat and death. And it was his experience of home and family that provided the inspiration for his creative expression.

As he wrote, ‘When I cast off on the voyage of my life, I felt like a ship made of old, rotten material sent out into a stormy sea by its maker with the words. If you are wrecked, it’s your own fault and you will be burnt in the eternal fires of hell.’ Not the most inspiring message to set sail on.

Edvard Munch came from the bourgeois suburb of Christiania, just outside Oslo, a society redolent of protestant hypocrisy. The state controlled brothels were regularly inspected to ensure that their upright clients did not take VD back to their protestant wives. But the Munches were more bohemian; middle- class priests, scholars, artists and poets with elements of genius and degeneration. His father was an impoverished army doctor. His wife, Laura, was one of his patients and half his age, but she shared the same deep religious convictions. They had five children in seven years but it exhausted Laura. She died of TB when Edvard was just 5. Karen, Laura’s sister, brought a breath of fresh air into the family home. It was she who encouraged Edvard to draw. By the age of 12, he was spending many hours a day drawing. But Edvard’s father was not consoled by Karen; he sank into his own introspections and used to frighten the children with stories of Edgar Allen Poe and warnings that their mother was watching them. Edvard suffered from nightmares and nearly died of TB when he was 13, and the following year his elder sister, Johanna died.

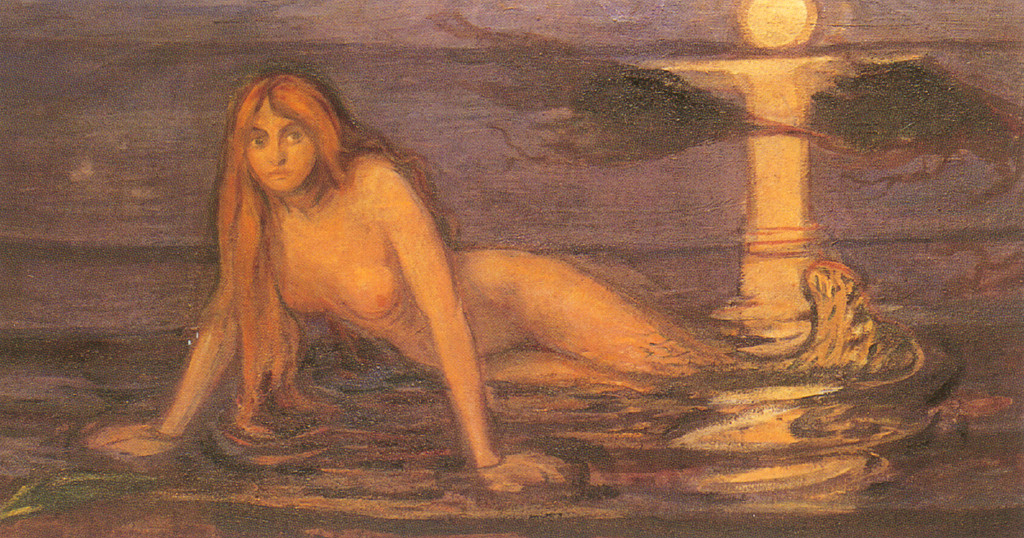

But Edvard found solace in drawing and painting and confidence in his success. At 22 he exhibited his work at the World Fair in Antwerp and was embarking on an affair with a married woman. ‘Young and inexperienced from a monastery like home, knowing nothing of this mystery, I met a salon lady and stood before the mystery of women.’ No doubt this ‘education’ informed his depictions of women as vampires, creatures that would seduce, tempt and destroy men. ‘Behind the prettiness lies death; the medusa’s head.’ Whereas Ibsen was writing about the entrapment of women by marriage, Munch saw men as the victims.

In 1889 he went to Paris, where he came into contact with the Impressionists, but it was Van Gogh’s suicide that probably had the greatest impact on him. The shock opened up a space in Edvard’s painting. He came to believe that painting should not just be about representation, it should express those feelings, emotions, states that you couldn’t see.

‘People will understand what is sacred in them and will take off their hats as if in church I shall paint living people who breathe and feel and suffer and love’.

In 1892, Munch was invited to exhibit his paintings in Berlin, but his exhibition upset the sensibilities of the narrative, romantic style of German art. Munch painted it as it was. His Frieze of Life, depicted the trajectory of a love affair through the kiss, love, pain, jealousy, betrayal and despair. Painting for Munch did not express one moment, but could, like a poem or a novel, illustrate an unfolding narrative. The exhibition was withdrawn after a week. This pleased the entrepreneur in Munch immensely as he realised that the negative publicity would do him nothing but good.

But appeals to his darker needs were never far away. His relationship with Tulla Larson, the 30 year old unmarried daughter of a rich wine merchant was one from which neither would ever recover. He was shocked and frightened by the strength of Tulla’s passion. He expressed his regret that this on-off affair has robbed him of 3 years of creative life and the use of his left hand, which was wounded when his pistol was accidentally discharged during their final argument. Bereft and traumatised, he threw himself into excesses of work, drink and gambling. He became ill, paranoid, developed hallucinations and in 1908 broke down and was admitted to Dr Jacobsen’s clinic. In time, he recovered and carried on working until his death in 1944, though some said that the life, the intensity had gone out of his work.

Before I knew anything about Munch, I was using his images to illustrate my talks on the bodily expression of human emotion. His expressive paintings capture the anguish of emotion more clearly than any other artist I know. He was a man on a mission, a mission to discover meaning through the depiction of love, fear,melancholia and death. He believed that you had to spill your guts for art. So Munch made art from his life, his depressed sick childhood, the deaths of his mother and sister, his morbidly introspective father, his tortured romances. He marketed the flaws in his personality for people to recognise and identify with. He offended people, of course. Even Adolf Hitler regarded his work as degenerate art. With such enemies, however, he had no need of friends. His legacy was assured. His emotionally charged landscapes had launched the German expressionist movement while his ability to get under the skin to the raw bleeding core of his subjects inspired such contemporary masters as Frances Bacon and Lucian Freud.

Schopenhauer once wrote, ‘The limit of the power of art is its inability to reproduce a scream.’ Perhaps Munch wished to show him his error.