There, but for the grace of God; a perspective on psychosis.

You’re driving me mad, I’m going crazy, I’m losing my mind, he’s just daft, it just doesn’t make sense! How many times a day do you hear such sentiments? How often do you express them yourself? Our lives are so complex, so pressurised that we have to work very hard to keep things together. And yet, we don’t see too many overtly mad people these days; most are medicated; a few locked up in institutions. But we can all show pockets of paranoia when our buttons are pressed. We can all go mad, especially if deprived of social contact and support. There is, however, a distinction between being mad and going mad and some people are just nearer the edge than others.

The medical term for madness is psychosis, which essentially implies having beliefs, attitudes and behaviour that are antithetic to social convention. Psychosis is not the only category of mental illness; there is also neurosis. The old adage captures the distinction nicely. A neurotic thinks that 2 and 2 equals 4 and is worried about it. A psychotic just knows that 2 and 2 equals five. So neurosis is a disturbance of doubt while psychosis is a condition of certainty and conviction. They are styles of being, different but not immiscible. Although people may try to evade the torment of neurosis by developing delusions , they can still be tortured by convictions of victimisation, devastated by fears of fragmentation. Life for somebody who is psychotic, can literally be hell! Even when things are calm, there is no peace from their internal thoughts and voices. No wonder so many people who have a psychotic breakdown, chose to end their own lives.

The problem is not so much how we can distinguish between neurosis and psychosis but how we can we distinguish each from so called ‘normality’. ‘Normal’ is a social construct, defined by reference to the culture a person comes from. The Christian notion of God, his reincarnation as Jesus Christ, the virgin birth and the resurrection, is considered quite normal in the United States of America and much of the western world. But as Richard Dawkins has emphasised, what is God but a massive delusion? The only reason a religious conviction is not considered mad is that the same delusion is shared by others. Falling in love is another delusion that is widely encouraged by society even though it has such massive potential to shatter a person’s private web of meaning.

Psychosis is a distortion of meaning and as such, a logical consequence of being human. We can all go a bit mad at times. Human beings are creatures of meaning, compelled to find reasons for their existance and what happens. They have a big brains that can see into the future, and a deep seated fear of what might exist in that void. They have the imagination to invent stories and can be both comforted or tortured by the delusions they create.

Meaning develops through relationship with others, initially our mother, father, brothers, sisters, grandparents and later, a wider circle of family and friends , teachers, mentors, books and television. It is conditioned by society, represents society and maintains us within that society. Therefore, if we regard psychosis as an alternative or distorted state of meaning, it is a social disease. It stands to reason that those who grow up isolated, conditioned by perceptions that are incompletely normalised by others, develop their own fragile belief structure that can set them apart from others. Alone in a black and white world, where people are either idealised or denigrated, they can tend to be suspicious and blame others. All the good stuff is located in themselves while the bad stuff is projected out though the opposite may attain.

But there are shades of isolation. People who live on the cognitive borders of society are able to function quite normally for much of the time, but may exhibit uncompromising and paranoid ways of thinking when their meaning is challenged. Mental illness might be regarded as a defence against the loss of meaning induced by change.

As creatures whose identity is created from meaning, we are all vulnerable to change. Any of us can be overwhelmed and devastated by an event that is completely outside our experience, and most of us, especially the more solitary, adopt strategies to prevent the devastation caused by a breakdown of meaning. Some may assume an idealised persona, a special identity that offers a role and purpose. This may be reinforced by special musical, literary or artistic talents perfected through the years of isolation. Others may mould themselves to their environment, sensing what others want and adapting to it. Women are said to be better at this, readily adapting their personality to the needs of a new partner. And finally some keep it all together by encapsulating themselves in an all consuming interest, an obession for work, a dedication, a faith.

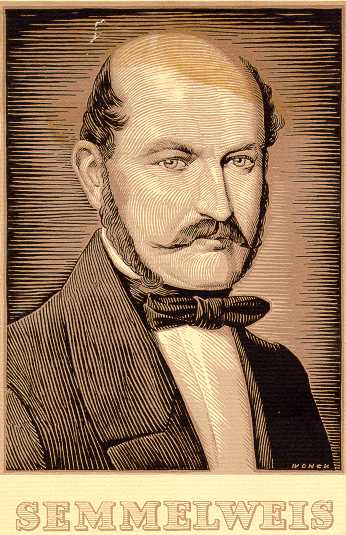

We can see examples of such behaviours in our colleagues, friends, family and in ourselves, but some people are more fragile, more susceptible to change and more clearly defended against it. But fragility is no reason for segregation. Society needs to achieve a democratisation of belief and thought. People with conviction and creativity can be exciting and inspiring. Most effective politicians have some spark of madness in them. They can be dangerous unless reined in by their civil servants. Society advances, not by the most stable, healthy members of society, but by those independent thinkers, who may at times be considered mad by their colleagues. Darwin, Einstein, Newton, and many of the great writers, artists and composers have all been considered mad at times. Ignaz Semelweis, whose hygeinic principles saved the lives of millions of women from puerperal fever, spent much of his life incarcerated in mental institutions.

Some of the ideas in this article were inspired by a talk on psychotherapy and the psychoses given by Darian Leader at the Biennial Conference of the Hallam Institute of Psychotherapy on October 2nd.

At last, smooene comes up with the \”right\” answer!