Gabrile Orozco; meaning out of chaos.

Gabriel Orozco is like his ball of plasticine, Yielding Stone 1992, rolling along, always on the move, always picking up new ideas, things from the streets, imprints, objects, impressions. He installs whatever he thinks is interesting, often distorting them to remove their utility, change their function, so that they engage more closely with the viewer as a work of art, a receptacle for meaning. In one installation (Lintels 2001), he gathered the plaques of felt from the filters of spin dryers, with their residues of hair, nails, grit and paper, and hung up on wires like washing lines. When this was exhibited in New York in November 2001, the ash coloured skins of lint with their message of the transience of human life, took on a poignant significance; something about the residues, the impermanence of life. In Carambola with pendulum 1996, he distorts the billiard table and suspends one ball on a wire so that it swings over the table. The players make up their own rules; hit the other white ball into the swinging red, strike the red so that it swings high over the edge of the table, position the other white ball so that it is in the path of the red. In Dial Tone, 1992, he slices the pages of the New York phone book and places the anonymous digits next to one another on a 10 metre roll of Japanese paper. It’s a measure of the city. In La DS, 1993, he cuts a Citroen car in three pieces, removes the central section and rebuilds the car in an aerodynamic form without an engine. It’s beautiful, creates an impression of a contender for the land speed record, but totally useless.

Orozco loves to play, to invent, he is fascinated by the meaning in everyday things, as a child would. While he was artist in residence in Berlin, he bought a yellow Schwalbe, a motor scooter, and then roamed the city looking for a partner, another yellow motor scooter, photographing the pair wherever they met (Until you find another yellow Schwalbe 1995). In a five star hotel in India, he was given three rolls of toilet paper, so he fixed them to the arms of the fan in his room, so that the paper streamed out with the rotation like pennants, and danced to it, Ventilator 1997.

Orozco explores the pattern of things, their organisation from chaos, their reordering into art. He collects the bits of blown out tires he finds at the side of the motorway and arranges them like black crocodiles on a white sheet of paper, Chicotes 2010. In Black Kites, he imposes order on death by inscribing a geometrical black and white grid on a human skull. As a child, he was obsessed with planetary motion, the orbits, ellipses, circles. This obsession appears in his work, in Samurai Tree and Atomist Series 2006 and Four Bicycles; there is always one direction 1994, in which he slots four bicycles together, so that the wheels rotate in different directions. It might be a comment on the ambivalence of life.

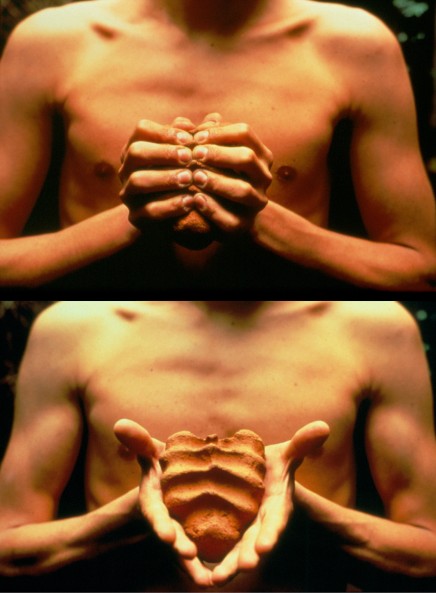

There is something touching and personal in Oroczo’s work, he is not afraid of expressing his childlike self, exposing his vulnerability. This is perhaps most movingly expressed in My hands are my heart, 1991, in which he shapes a lump of clay, of the same colour as his skin, with his hands then has this photographed against his chest, exposing, as it were, his heart.